‘Looking in the Same Direction’: Art and Technology at the Renaissance Society

Lydia Ourahmane and Alex Ayed, Laws of Confusion, 2021, installation view at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, photo: Useful Art Services.

By Ellen Wiese

For a few weeks in late 2021 and early 2022, the fourth floor of Cobb Hall was transformed into an elemental space suffused with haze, purple light, and the amplified music of an audio jammer. Long black plastic gloves reached up from the floor. A few feet away, a fluted decanter held water from the Nile River. A sealed container of lithium accompanied a set of packages on a digital scale, a box fan, and a table of audio equipment.

Curators Myriam Ben Salah and Karsten Lund at the Renaissance Society had been familiar with the work of Ourahmane and Ayed—in fact, Ben Salah had been responsible for connecting them a few years before. The curators were interested to see what the artists could create specifically for the space of the Renaissance Society, and as such, the exhibition was not a traditional show of existing work; it was as much about process as product, creating an open-ended show that evolved all the way up to the opening day.

They began by thinking about questions of communication—its possibilities, failures, and “beautiful fluidities,” as Lund puts it. Located in Barcelona, Paris, Tunis, and Chicago, the collaborators were keenly aware of the modern questions of technology and mediation as they worked together over the internet. “This flow of communication is something that brings a lot of confusion,” Ayed said in an artist talk at the exhibition’s opening. “Everything is true or untrue. We felt like we needed to actually do something with this.”

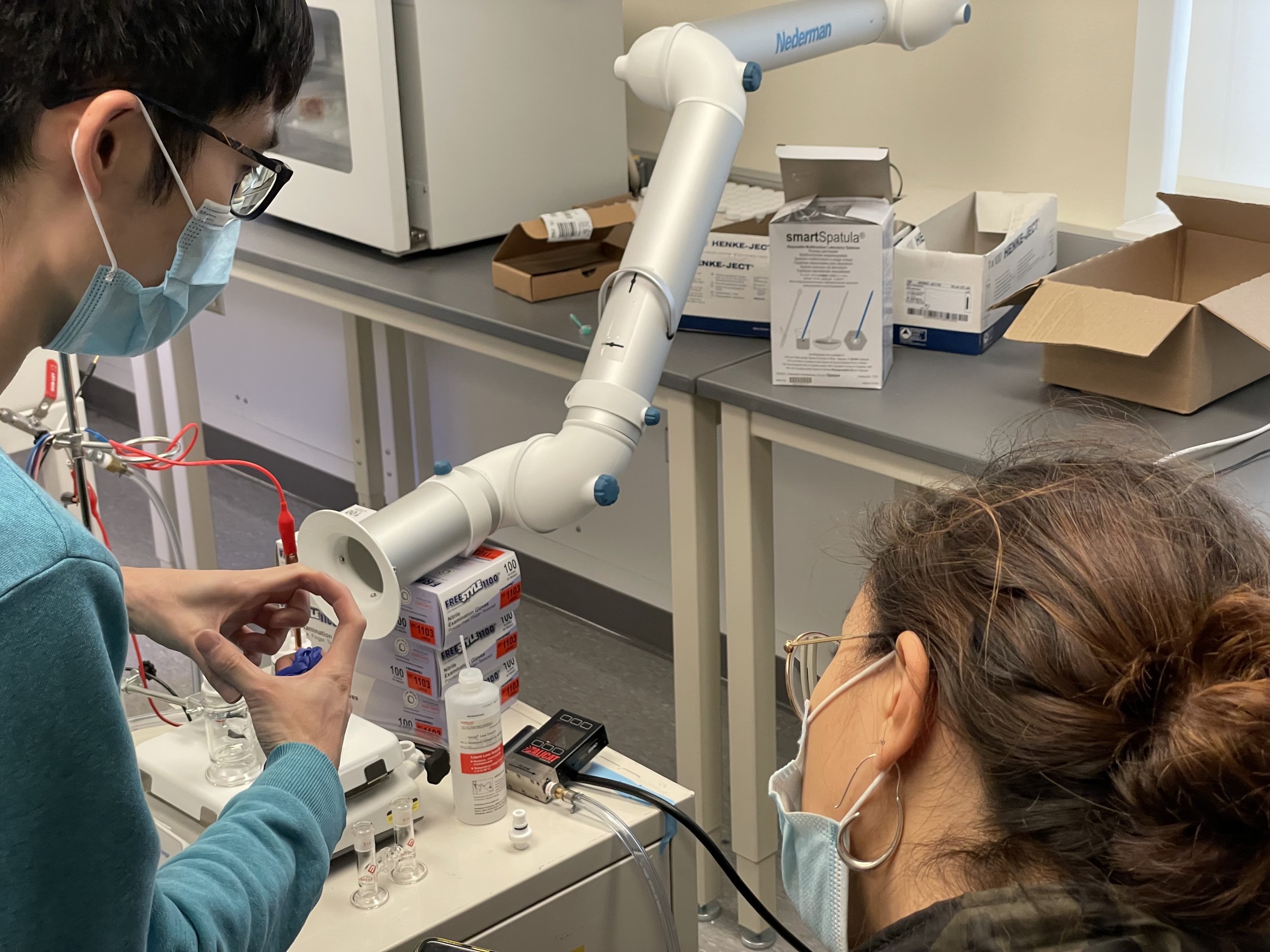

The pair considered modern communication techniques, Ourahmane added during the conversation, in particular the lithium batteries that power our electronic devices. “It’s really the container of the future of communication, before light,” she said. Julie Marie Lemon, Senior Director and Curator of the Arts, Science + Culture Initiative, connected the artists with the Amanchukwu Laboratory at the University of Chicago, an electrochemical lab that works on developing sustainable energy technologies. Over the next weeks and months, the artists and curators worked with Principal Investigator Professor Chibueze Amanchukwu and PhD student Peiyuan Ma to develop their ideas into a workable solution.

Ma walks Ourahmane through the laboratory’s research.

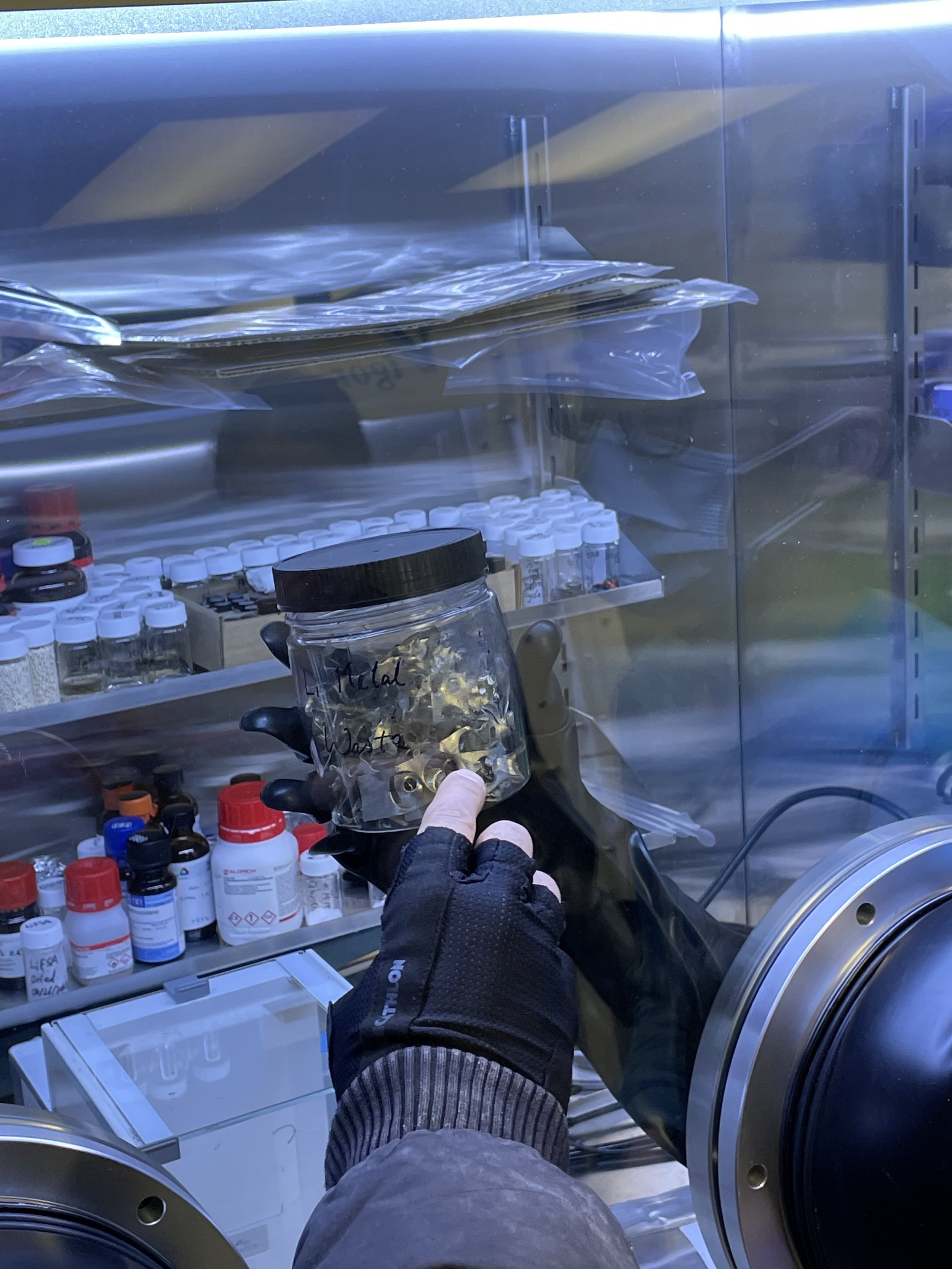

Initially, Ourahmane and Ayed hoped to create a sculpture of pure lithium. But as the scientists informed them, the element is highly reactive; even the slightest contact with air will cause it to catch fire. “It’s a bomb,” Ma says with a laugh. “You cannot take it out. It will explode.” The scientists work with lithium in a “glovebox,” carefully sealed in an atmosphere of argon, using built-in plastic gloves. In visits to the laboratory, the artists were able to see this setup firsthand. In the end, they opted to display a sealed package of lithium in the exhibition alongside inflated gloves of the same type used in the lab. “It became as much about its latent possibilities as something that had actually been sculpted,” Lund says. “You have to imagine what’s inside and you also have to imagine a million other things that might spin off from there.”

Researchers at the Amanchukwu Lab use this “glovebox” to handle dangerous materials like lithium.

In some ways, the inability to directly handle lithium was disappointing. But it also highlighted new possibilities. “It felt so wrong, so against the nature of that material, to try and sculpt it,” said Ourahmane. “It was more this idea of making a figure, or building an image, with something so impossible and something that had the potential for so much.” The potential in limitation and absence was a recurring theme in the exhibition’s creation. During the development process, Ourahmane and Ayed traveled to Cairo, where they hoped to gather the soil of the Nile River.

They were curious about what Lund described as “a dance within the show between some of these more elemental materials and materials that have more technological shadows.” Moving clay from Egypt, however, is strictly forbidden by law, and in the end only river water was able to make the journey. “I think we enjoy resistance,” Ourahmane said of the process. “At the end of the day, let’s be honest, we are very drawn to impossible situations and materials, and friction. We love to deal with that space. Is there a way through something that’s impossible?”

This attitude is shared by those at the laboratory: “What’s impossible now,” Amanchukwu says, “will be feasible in ten years.” He found the experience of working with the artists, and seeing the familiar elements in a new context, uniquely exciting. “I never thought of them as art pieces,” he says of the lithium and gloves. “These are a means to an end, we use them to get results, and it was refreshing to see the story one can tell with these artifacts, a different perspective on something I’ve been working with for almost a decade.” Ma agrees: “This is something new to me,” he says. “There’s a saying that scientists should be artists at the same time—they’re just artists in another field. After this collaboration, I did feel that art has something in common to what a researcher like me does. It felt like talking about a research topic with a colleague.”

Lydia Ourahmane and Alex Ayed, Laws of Confusion, 2021, installation view at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, photo: Useful Art Services.

That alchemy—the collaboration and sharing of perspectives—has been a key element of the process for all involved. “The genuine willingness to be there and to give has been something that I will take away from this, from the experience of Chicago,” said Ourahmane at the opening. “It’s been a lot of generosity from everyone who’s worked on the show.” The exhibition, according to Ayed, is just one step in a bigger conversation, a larger chemistry experiment. “In the popular imagination,” Lund adds, “people can sometimes speak as if art and science are on wildly different ends of some kind of human spectrum. But there’s a lot of shared terrain. There’s a sense of hypothesis and experimentation. There’s a real openness to what’s happening around you. Their imaginations might be directed at slightly different angles, but in some ways they’re all looking the same direction.”

The Arts, Science + Culture Initiative cultivates collaboration, active exchange, and sustained dialogue among those engaged in artistic and scientific inquiry within the University and beyond.

Learn more about the Arts, Science, and Culture Initiative.