The Blues in Community & Conversation: an interview with Matthew Skoller

In curating Blues Geographies, Matthew Skoller leans into how music connects - even when genre tries to keep us divided.

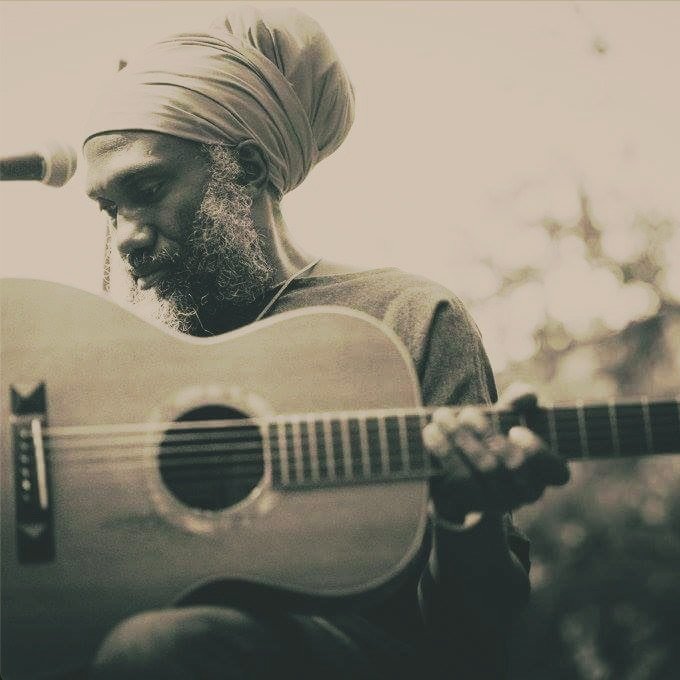

Matthew Skoller | photo by Al Brandtner

Matthew Skoller is one of Chicago’s most respected harmonica players and Blues bandleaders. For the past 36 years he has played all of Chicago’s heaviest showcase venues and toured much of the world with his super tight ensembles. Deeply rooted in the tradition of the Chicago blues elders with whom he worked and studied, Skoller has developed a unique style that conjures the past while being firmly planted in the present. He is also a curatorial partner for all things Blues at the Logan Center. He sat down with Jess Hutchinson, Editorial Content Manager to talk about the April 1st Blue Geographies event at Logan - and about the shared histories and false divisions driven by corporate greed and white supremacy culture in American music.

Jess: So, I was a little tardy to start this meeting because I was watching videos on your website of you perform and I couldn't stop watching those in time to be on time for this interview. That's just praise. There's not a question in there. So, to get going, I would love to hear from you how your relationship with the Logan Center started.

Matthew: Leigh Fagin [the former Director of University Arts Engagement] put out a memo to her contacts within the Blues community that she was looking for a director for the Logan Center Blues Fest. And when that memo came out, I got two phone calls immediately: one very close colleague, and then there was another gentleman who was sort of a fan, I guess, peripherally involved in the Blues world, who saw the memo as well, and emailed me and said this has got your name all over it. They needed somebody who was going to be a liaison between an academic institution and the Blues community, somebody who's had experience in both and both of my parents were professors. My oldest brother is a film artist who has been a professor of cinema at UC Berkeley, and actually taught at the Art Institute of Chicago for a few years as well. And so I grew up on campus and so I was able to show that I could navigate both those worlds in a way that would be beneficial to the Blues Festival and the rest is history. I met with Leigh and I got the gig.

Jess: So, how have you seen the relationship between the Logan Center and the Blues community change or grow – metamorphosize maybe – since you first started working with the Logan Center?

Matthew: You know, I think that Blues artists are really impressed with the Logan Center, and the Logan Center has shown that they really respect what Blues artists do. They give them the kind of treatment that they deserve, which is normally not the case, and they also remunerate them in a way that is appropriate. And so, they've got a really great reputation amongst artists who have worked for them because of their thoughtfulness, their hospitality, their respect. They also, for those of us who have a part of ourselves that cringe when we see Blues relegated to you know, Budweiser sponsored BBQ events – not that beer and BBQ isn't awesome. We love it and we do it at the Logan Center too, but. But it's not the main attraction, you know? It’s something that you do to celebrate the fact that we have this incredible legacy of Blues music in this country. I mean, the thing that we acknowledge through our programming at Logan Center is that Blues is really a special genre. I mean, it's a genre that has literally changed world music in a super profound way. And it's not just a musical genre, it's also a cultural, you know, appendage to African American culture.

And so that and that is an interesting line to walk. You have to be cognizant of the social symptoms and the ills that Blues was born out of. But you can't relegate it to simply that because it's also a highly wrought art form and to relegate it to a set of social symptoms is very problematic. And so, I try not to do that in the way that I address the programming and the artists and Blues at the Logan Center. And I think I've been pretty successful at that, but also in a climate where there is most definitely industry-wide appropriation going on, where Black artists are being omitted from programming and not being included on the stages that their ancestors built is something that has to be acknowledged and dealt with. And I think if you look at our programming, which is inclusive, but it's also very, very heavily based upon artists who are direct descendants from that culture. And part of the reason for that is that when I was charged with curating Blues at the Logan, I was told that one of the things they were most interested in is exploring the intersections where other artists from other disciplines meet the Blues. And so I've brought in poets whose work is totally inspired by Blues music. I've brought in actors and playwrights who come out of that tradition of August Wilson, which comes directly out of Blues music. Consequently, those artists are going to be African American. You're not going to find, you know, too many Swedish painters who are inspired by the Blues. I'm not saying they don't exist. Or that their work wouldn't be really interesting, but you know it's not exactly where you begin.

Jess: Yeah, that makes sense. So, I'm thinking specifically about the upcoming the Blues Geographies program and would love to hear you talk about the decision to put these two artists – James Leva and Corey Harris – in conversation and the idea of Celtic immigrants and enslaved Africans and their descendants bringing their musical traditions together.

Matthew: Well, I mean music is music, you know. And that's the thing about genre: for the most part (and this is something I've learned doing the programming at Logan; I had inklings of it, but actually being involved in it and really unpacking it has taught me a lot) you find that genre is really a tool created by monetizers that is weaponized to create markets. So when you take a look at what happened in American old time country music, you see that it was poor folks who ignored the laws of slavery or Jim Crow and who didn't care about the differences, but were much more interested in making music with each other. And that’s the beginning of Americana: all of these musicians who find themselves in the same economic position – poor – getting together and sharing the richness of their musical legacies and histories. And that's where Blues comes from.

The banjo’s roots

This 18th century painting, The Old Plantation, includes a depiction of a man playing a banjo-like gourd instrument. Learn more about the roots of the banjo at the Black Music Project.

But it's not just where Blues comes from, it's where country music comes from, too. And so when we look at the erasure of African American foundational contributions to the evolution of country music, we see the monetizers who were salivating at the prospect of selling millions of records to different niches. As the record industry really became a big business, you can see how they started to rewrite history and started to try and steer the music into certain corrals. And so, this is why we bring Corey Harris and James Leva together, because they both come out of the same background of these roots musicians who developed together and created beautiful, beautiful music.

When you take a look at what happened from the beginning of the 20th century: the banjo and the violin were ubiquitous, and they were the prevailing instruments in the old timey country stuff. When the 1920s came and these monetizers, who were making records for Italian immigrants in Italian, making records for Irish immigrants, making records in German – and they found small little niches of each of these immigrant cultures. So, when they heard that there was this new music emerging in the Black community called the Blues, which was really just in its inception, everything had to be a Blues song if it was going to be marketed to the Black community, which was done by design of basically racist businessmen. Number one, they put the word Blues onto songs that had nothing to do with the Blues. And then the other thing is that they literally told a lot of Black master musicians that they wouldn't put their records out if they played the violin or the banjo. You know, Lonnie Johnson was one of the most seminal guitar players in the history of Blues music. But he was a super accomplished violin player too, and there are only a couple of recordings from the mid-1920s of him playing the violin. So they were relegating the fiddle and the banjo to white country music, and they even gave the banjo a face lift: they took a tambourine and made into what we know now as a white country instrument. And it very isn't. It is an African instrument. People like to also say that the violin is European, so you've got the European instrument next to the African instrument, the violin and the banjo, (and that's problematic because a lot of cultures have an instrument that resembles a violin).

Scottish & irish Immigrants brought their fiddles

Learn more about the Scottish and Irish immigrants who brought their music - like tunes by Neil Gow featured in this painting by Sir Henry Raeburn’s painting - with them to Appalachia.

But all of that aside, there was really a lot of manipulating going on. The elasticity and malleability of music in general was corralled into these very neat genres that really don't exist. When you listen to certain artists, you hear that. I mean, listen to Etta James. What is she doing when she's singing Billie Holiday, is she singing jazz? What is she doing when she's singing a pop tune? What is she doing when she's singing a deep Blues song? What is she doing when she's singing the early R&B that catapulted her into stardom? She’s playing Black music. That's what she's doing, and it's all part of one another. I think that one of the things that my programming tries to celebrate is the reality that the over-dominating aesthetic of African American music is pushing the envelope, pushing the borders, changing it, making it a part of the moment that they're in, right now, using technology, using the changes in society that can happen at the flick of a switch and influence how these artists see the world and see their music. And so, why is this such a prevalent ingredient in Black American Music? I'm not saying I know the answer to that, but it does seem to me that if you're kidnapped from your homeland. And your religion is taken from you and your instruments are taken from you and your family is taken from you, and you are living in this sort of limbo, that you find ways of reinventing yourself and your family and your music and your religion to survive.

The whole of American culture is designed to create division and differences and resentments. It's divide and conquer, what they've done so successfully for centuries here.

Jess: And do you – do you think that … the Blues can heal the world?

Matthew: I think music in general – that's what music is really. You know, it's a way to heal one another with sound and with spirit. It's not just Blues it's all music, you know.

Jess: One of the things I’m intrigued about with the Blues Geographies program – in thinking about music as care: there's a part of this event where there is food. So, people will enjoy the healing potential of the music. They'll see these different pieces and they'll be in community with each other, especially as we're still kind of remembering how to do that…

Matthew: Food has always been a huge part – even at house parties and juke joints in the Deep South, food has always been a component of it, you know? And it would be just as egregious an omission to not break bread and not provide delicious sustenance before, during or after the performances, as it would be to only market Blues as a party favor. And so you strike a balance, and I definitely see that as part of the vibe at Logan Center. We definitely include food every time we possibly can, and you know there's Café Logan where you can get a glass of wine or a beer – there's libation and there's a lot of good food brought in over the period of the Blues Festival. That's all part of it.

It's just that a lot of the conversations that need to be had around Blues music are not being had and what is the environment where these really important conversations can take place? It's just not as conducive at a football field or a speedway or a Blues bar you know to have really important discussions that need to take place. I mean, there's this thing called white supremacy that has to be discussed, you know. And it's a huge, huge component of how the Blues industry has evolved or devolved depending upon how you look at it.

And I think that at Logan Center, whether or not we address that directly, it inevitably happens in conversations because that’s the nature of the programming really. It illustrates how you cannot separate this music from the people who gifted it to the world.

Jess: Yeah, I keep thinking about how when anybody talks about Elvis, they don't usually talk about where Elvis got his sound.

Matthew: And when we talk about country music, even when they do acknowledge: so many of the greatest country western legends and forefathers, all had lessons from African American master musicians. You know who taught them how to play their instruments? And that's why there's so much Blues in country music. The techniques that they use to play their instruments came out of these Black Blues artists. So you get all this, “yes, I tutored under them and they were my mentors and they were influencers.” And I choose my words really carefully: I’m talking about foundational contributions. Not about teaching somebody how to flat pick or bend a string. Because the implication is that once the white artists got the techniques, they elevated them and took them to a place that the Black musicians couldn't and that is nonsense. They were just living in a white supremacist world where anything that a white artist did was way more marketable than anything that a person of color did.

You have to be careful about the language that's used when even giving props. A good example is the Carter Family, which is generally considered to be the first royal family of country music. AC Carter, one of the Carter Boys, went out looking for songs and he got songs from Black musicians and white musicians. He combed the countryside. Problem with him was he couldn't remember melody. And so, he could write words down, but he couldn't remember melodies. So, they found Lesley Riddle, who was an African American musician who had a great audio memory and they called him a human tape recorder. They would go out and find the tunes and Riddle would go home and transcribe the melodies that he had heard. Now, anytime you're transcribing something from memory there's a whole lot of you in it. And you're also interpreting, so a lot of these melodies that became the songbook for the Carter Family came directly from Lesley Riddle's pen, and it also came from the places where Riddle heard them. One of the most famous examples of this a spiritual that the Carter Family learned from Lesley Riddle called “When the World's on Fire.” And so later they took this Black spiritual melody and recorded it with different lyrics, and it was called “Little Darling Pal of Mine.” And then eight years later a guy named Woody Guthrie, who was famous for taking songs that were already songs and putting his own topical lyrics or his own poetry to them, took it and wrote a song called “This Land is Your Land.” And this is just the tip of the iceberg. And so yeah, Elvis definitely grabbed “Hound Dog” from Big Mama Thornton and most definitely was schooled by Little Junior Parker and JB Lenoir, taking Elvis into the Black neighborhoods to study the movements and the sounds. And Sun Records, Sam Phillips, was very clear that he was looking for a white guy who sounded Black. And so, they groomed him, and then they destroyed him. But yeah, it's a tradition that goes way, way long before Elvis, and it's still happening today.

The Carter Family

“When the World’s On Fire”

The Carter Family

“Little Darling Pal of Mine”

Woody Guthrie

“This Land is Your Land”

Jess: So, if you could whisper into the ears of everyone who's going to come to Blues Geographies, what’s something they should consider while they're enjoying their BBQ and enjoying this music from Corey Harris and James Leva? What might you whisper to them?

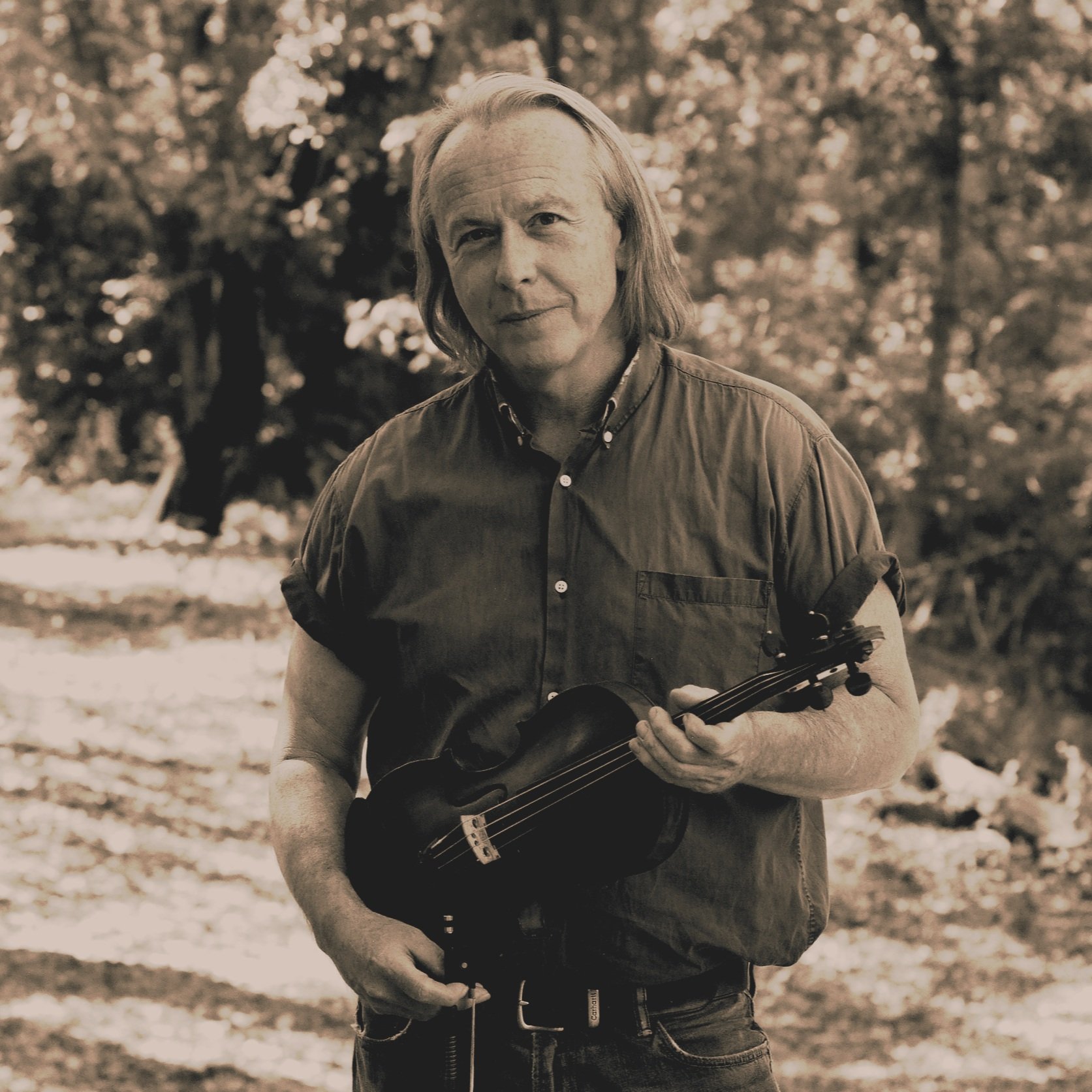

Matthew: The notion of genre is an often limiting and sometimes dangerous construct, and we need to stop drawing lines around art that is by nature malleable and ever changing. And there's a place for archivists, and there's a place for traditionalists. But that can be taken to a point where it kills the music, and we don't want to kill anything. So, I think that that would be an interesting thing for people to reflect on while watching folks like James Leva and Corey Harris. And I will tell you that both of these guys – you listen to their music and it is so real and so immediate. But these guys have studied all of what we're talking about and they are some of the world's foremost experts on the conversation that we're having right now. And they are both extremely accomplished communicators and so I really wouldn't miss this one, because you're going to not only see and hear the brother and sisterhood between these different incarnations of American music, you'll also hear some really articulate guys talking about the history and the evolution of it, so it's going to be fascinating, it's going to be fun and it's going to be real so get your reservation.

Get your free tickets for Blues Geographies featuring Corey Harris and James Leva, Saturday, April 1, 7:30pm at the Logan Center. For $10, you can enjoy the pre-performance Blues BBQ dinner at 6pm. Vegetarian & vegan options available. Blues BBQ is catered by our South Side partners, I57 Smokehouse Chicago and Majani Soulful Vegan Cuisine. More info and tickets can be found here.

Blues@Logan Center is made possible with the generous support of The Jonathan Logan Family Foundation with additional support provided by the Chill Family Fund for the Logan Center for the Arts.