PUBLIC ART ON CAMPUS

Jene HighsteiN

(American, 1942-2013)

Interview with Jene Highstein, sculptor, conducted by the STONE Project at Edinburgh College of Art, UK.

The STONE project was a three-year project (2007–2011) based at Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) and funded by the AHRC. It sought to re-appraise the use of stone in art and the contemporary environment and to gather together ‘the many perspectives, attitudes, and processes that we have observed in those who work directly, or share a conscious connection, with stone’. Specifically, the project sought to document endangered stone working techniques and craft skills in order to conserve them and transfer them to future generations. The project placed particular emphasis on the distinctive modes of thought associated with stone-working, including ‘haptic thought’ (thinking through touching) and ‘reductive’ or ‘subtractive thinking’ (in contrast with the more frequently encountered additive mode of thinking, i.e. modeling up). Learn more about STONE >>

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

After completing a philosophy degree at the University of Maryland (1963), Highstein became interested in fine art during his graduate studies at the University of Chicago (1963-1965). He took up painting at the Midway Studios while working on his philosophy thesis on notions of space in Renaissance theories of perspective. In 1965, he chose to abandon his studies entirely in order to pursue a career as an artist.

While studying drawing in New York (New York Studio School, 1966) and London (Royal Academy Schools, 1967-70), Highstein took note of the work of his contemporaries in exhibitions such as Primary Structures (Jewish Museum, New York, 1966) and When Attitudes Become Form (Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1969). His first solo show was an installation at London's Lisson Gallery in 1968, which laid the ground for an ever-evolving sculptural and spatial practice that would span close to half a century. Upon his return to New York in 1970, he immediately became an instrumental figure of the city's alternative art scene, closely associated with both the Institute for Art and Urban Resources and the Anarchitecture Group at 112 Greene Street.

The geometrical approximations and primordial associations of Highstein's post-Minimalist work betray the intense attention to materials that informed his practice through the years. From the raw and hollow constructions in industrial materials (concrete, steel) of the early years, to the polished and carved natural materials (granite, wood) of his work since the 1980s, and the iron castings that bridge the two, Highstein's artistic practice revealed his roots as a student of philosophy and persistently investigated the relationship of sculpture to its spaces.

Written by a uchicago student in the Spring 2015 Public Sculpture class

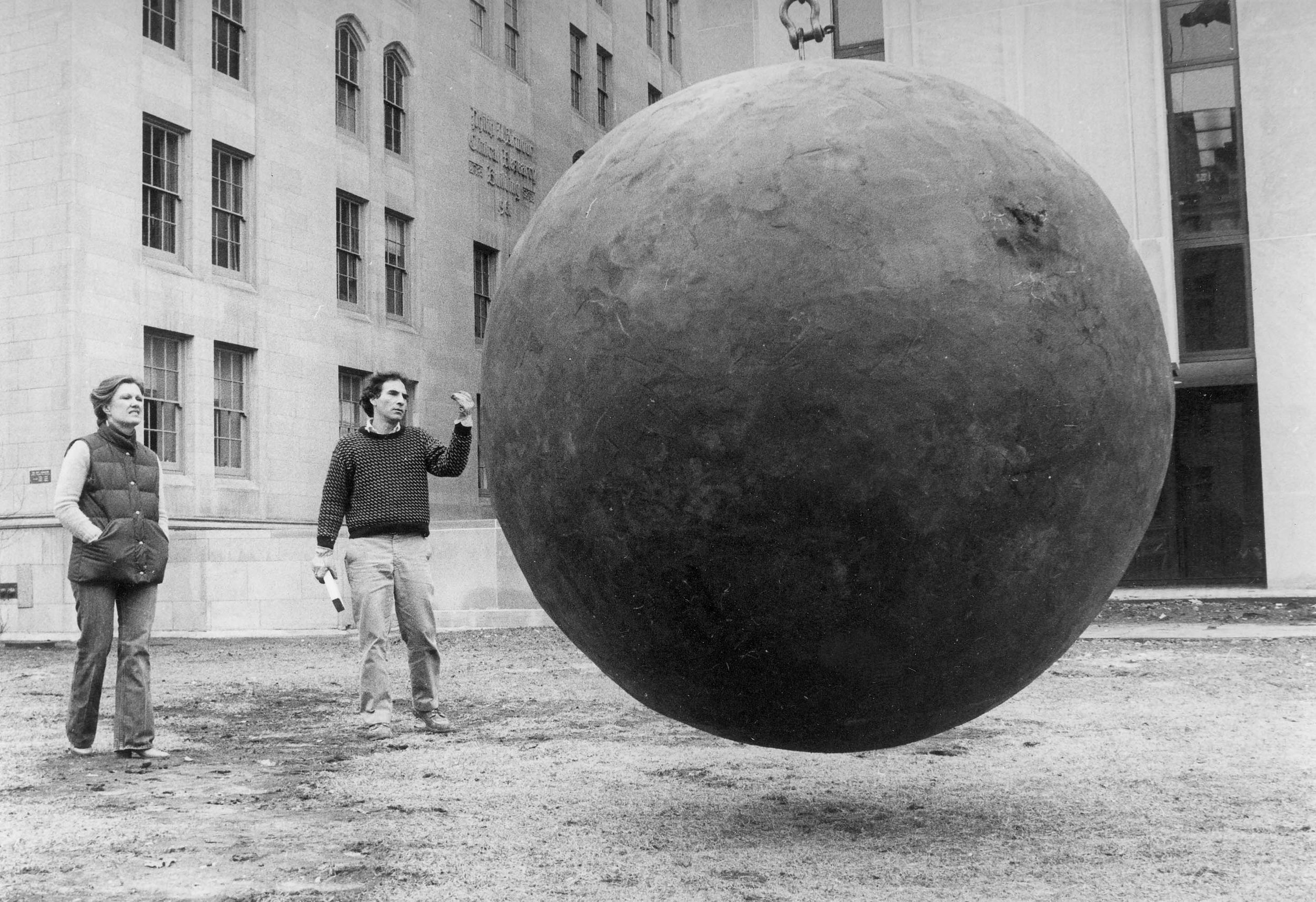

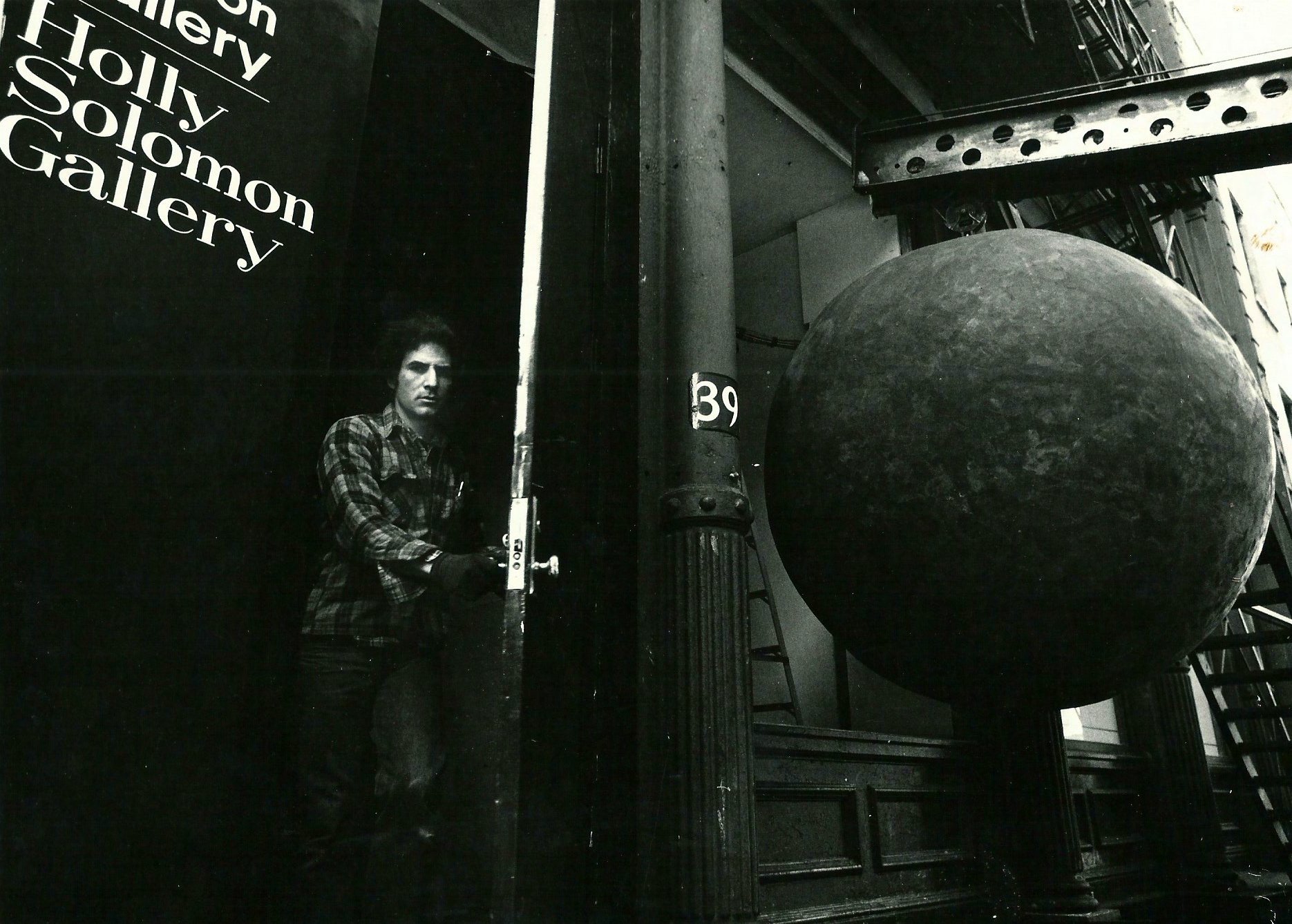

BLACK SPHERE, INSTALLATION VIEW, 1980.

Black Sphere

Created 1976 / Reconstructed by the artist 1985 / Current installation 2022

Painted cement over steel structure

Height: 72 in. (182.9 cm)

Diameter: 76 in. (193 cm)

Located at Gordon Center for Integrative Science

929 E 57th St, Chicago, IL 60637

Donated to the University by Betsy & Andy Rosenfield

in honor of Lindy & Edwin Bergman (former Chairman of the Board of Trustees)

“The density...generates an awareness of one's own physical weight and mass in relation to the sculpture. Comprehending [Black Sphere] is an intuitive rather than deductive process—one of body empathy and movement through the space in response to the object.”

—Michael Auping, “Jene Highstein/MATRIX 26”

About BLACK SPHERE

Black Sphere is one of five black concrete sculptures created by Jene Highstein between 1975 and 1977, with a distinctly spherical shape that sets it apart from the other four mound-shaped works. Where the latter are firmly grounded, rising gradually from the plane upon which they rest, Black Sphere sits precariously, perched like a ball about to set in motion. Movement is more than merely formally invoked, as Black Sphere has traveled extensively from its initial installation at the Holly Solomon Gallery in New York in 1976, to its current siting on South Ellis Avenue in Chicago.

This is no mean feat for a 3,000-pound steel and concrete sculpture, whose industrial materials convey a density of mass that is only further accentuated by the opaque black surface of the sphere, stretching just over six feet in diameter. Despite the sense of solidity the sculpture imparts, its concrete surface is a mere skin. Constructed by the gradual application of concrete by hand to a mesh-covered, hollow steel armature, Highstein’s Black Sphere was achieved by a process of human approximation that is markedly different from the exacting industrial procedures of most Minimalist sculptors. It defies the formal expectations of regularity that its geometrically derived shape invites. Although it suggests all the industrial might of large-scale construction, Black Sphere is far frailer than it appears, and its many moves have necessitated numerous restorative efforts that have materially transformed the sculpture.

-

Black Sphere's series of transitory installations in the first years of its existence form an integral part of the sculpture's history and its place within Highstein's early artistic practice. Though seemingly introspective and driven by formal rather than social concerns, Highstein's early works were in fact deeply entrenched in the transformation of blighted areas of New York in the early 1970s. It was in these years, after Highstein's return to New York from London, that his sculptural practice found its own formal language. In post-industrial, recession-struck New York City (vast swaths of which were earmarked by Robert Moses for ever more invasive large-scale urban renewal projects), empty warehouses and former manufacturing plants provided alternative art spaces for artists.

In those formative years in New York, Highstein became closely associated with the artist community in and around 112 Greene Street, where he was a member of the Anarchitecture Group of artists, whose work responded critically (and often radically, as in the case of lead member Gordon Matta-Clark) to the radical transformations in their built environment. Highstein also worked and exhibited during that period in alternative art spaces—such as P.S.1 and the Clocktower—that were procured by the Institute for Art and Urban Resources, which was founded and run by his then-partner, Alanna Heiss. Highstein's installation and sculptural works in this era took the form of spatial interventions that were in dialogue with the temporary spaces and broader urban environment in which they were both created and sited.

Conceived at the height of this period of artistic experimentation for Highstein, and at the point of development of his distinctive formal sculptural language, Black Sphere marks a crucial shift in Highstein's practice from works that intervened into existing spaces, to discrete sculptural objects. From 1973 to 1975, Highstein created his works in the Condemnation Blight Sculpture Workshop in a defunct industrial beverage facility on Coney Island. The Workshop was an initiative under the Institute for Art and Urban Resources and was a WORKSPACE project, namely, “a program designed to turn unused urban buildings into studios and exhibitions spaces for artists.” The land that the Workshop occupied was leased from the city only until 1975, the same year Highstein began making his concrete sculptures. In this way, Black Sphere was produced at the threshold between Highstein's period of artistic experimentation, which was deeply embedded in the alternative art spaces of early 1970s New York, and the distinctive sculptural practice he developed immediately following, which moved far beyond the confines of the art capital of the United States.

Initially created for the commercial setting of New York's Holly Solomon gallery, Black Sphere has since traveled to several prominent institutions across the country. Before it arrived at the University of Chicago campus in 1980, Black Sphere had been on display in the University of California, Berkeley's Art Museum, where it was part of one of the earliest exhibitions in the MATRIX Program for Contemporary Art in the fall of 1979, thus travelling more than 5,000 total miles from its creation to its installation here at the University.

When Black Sphere first arrived on campus for its exhibition at The Renaissance Society in March 1980, its installation in front of the Brain Research Pavilion (across the street from The Renaissance Society's Bergman Gallery) was only ever meant to be temporary. However, following The Renaissance Society's initial installation, Black Sphere had proven so popular that it was chosen by Betsy and Andy Rosenfield, the children of Edwin A. Bergman (then-Chairman of the University's Board of Trustees), as a gift to the University in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Bergman's anniversary. In 1984, the sculpture briefly abandoned its home at the University of Chicago to travel to New York, where it greeted visitors as they entered the vast new gallery space at MoMA New York for the International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture exhibition. Comprised of nearly 200 works made since 1975, it was a monumental show of contemporary art planned for the inauguration of the MoMA West Wing expansion, and Black Sphere took pride of place.

When the sculpture was ready to return to the University of Chicago campus in August of 1984, it suffered severe damage in transit before it could be securely installed. While the specifics of insurance policies and restoration processes were being investigated, Black Sphere occupied a new, temporary space on a lawn next to the Lorado Taft Midway Studios until it was moved inside the building for restoration. Highstein worked with Art Department faculty members to mend the steel armature, apply new chicken wire, and apply a new layer of concrete by hand to produce the sculpture as it appears on Ellis Avenue today.

In this way, Black Sphere both originated and has been consistently sited in urban settings undergoing transformation. From the gentrification by artists in Lower Manhattan, through the MoMA West Wing expansion, to the University of Chicago campus, Black Sphere's sites have been intertwined with histories of art and artists' role in changing the built environment. As a result, Black Sphere presents to us a material manifestation of the complex negotiations between urban transformation and art.

Written by a student in the Spring 2015 Public Sculpture class

-

Black Sphere object label (PDF) written by Peggy Mason, Professor, Department of Neurobiology, for Monochrome Multitudes at the Smart Museum of Art, 2022.

Rossi, Laura Mattioli. Lines in Space. Milan: Charta, 2008.

“The Artist in Place: The First Ten Years of MoMA PS1.” MoMA, 2012. Online.

-

“Alanna Heiss and Jene Highstein, Parts 1 and 2.” The Clocktower Oral History Project. Clocktower. Part 1. Part 2.

Auping, Michael. “Jene Highstein: Black Sphere, 1976,” MATRIX/BERKELEY 26. Berkeley, CA: University Art Museum, August 1-October 31, 1979. Online.

Doe, Donald Bartlett, and Neubert, George W. “Jene Highstein: Shapes in the Stream.” Paper 39. Lincoln, NE: Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications, 1985.

“Oral history interview with Susanne Ghez, 2011 Jan. 25-26.” Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art. Transcript.

TRUNCATED PYRAMID, INSTALLATION VIEW. Christine Badowski

Truncated Pyramid

Created 1989 / Installed 1992

Carved marble

Height: 66 in. (167.6 cm)

Located in the Vera and A. D. Elden Sculpture Garden

at The Smart Museum 5550 S. Greenwood Avenue

Purchase, Gift of The Smart Family Foundation in memory of Dana Feitler

ABOUT TRUNCATED PYRAMID

Gifted in 1992 by the Smart Family Foundation, Jene Highstein’s Truncated Pyramid was the first work of art by a former University of Chicago student to be placed in the Smart Museum of Art’s Vera and A. D. Elden Sculpture Garden. The imperfectly shaped, white marble structure with faded pink striations bleeding down the sides of the work juts out of the grassy area around it, achieving a height slightly over five and a half feet.

Truncated Pyramid is one of two Highstein pieces located on the University of Chicago campus. Unlike the other, Black Sphere, which addresses the issue of space and mass as a function of construction (in which a hollow center is hidden by an overwhelming black mass), Truncated Pyramid explores mass as a form of removal. The large, two–ton piece of marble was cut from a larger stone, not carved into a polished form like the familiar tradition of Roman and Grecian marble sculptures. The imperfect, rough, horizontal cuts that run parallel along the surface of the 66–inch pyramid both maintain and transform the marble. The cuts minimize the amount of interruption to the object’s form and reveal a dense, solid core of a truncated (cut) pyramid. However, they also create a sense of fluidity and lightness that is not normally associated with rough, heavy stone. The piece counters our associations of mass as weight and instead introduces mass as an inversion; the cuts along the piece completely transform the solid marble structure to evoke lightness.

-

During the 1990s, and few years before, Highstein shifted his focus from a constructivist/additive process to one of removal. In his earlier works, like Black Sphere, the tension between space and mass was created by adding materials to a hollow cast. The change in material—from cement and steel to stone and marble—allowed Highstein to make subtle changes to the material’s form. By cutting away at the marble’s surface, Highstein changes the viewer’s perception of mass, working towards a contrast of experience and knowledge. Our perception of the piece is in direct opposition to our knowledge of the material. The marble becomes lighter, more fluid, and less dense, yet it still exists as two tons of heavy stone.

After its production in Portugal, Truncated Pyramid was quickly brought to the University of Chicago’s campus through the Rhona Hoffman Gallery. The work was gifted to the museum on behalf of the Smart Family, in memory and honor of Dana Feitler, a former student of the University of Chicago and the daughter of Joan and Bob Feitler. Teri Edelstein and other members of the Smart Museum staff presented Bob and Joan Feitler, members of the Smart Family Foundation, with several works of art to choose from. Their admiration of the carved marble piece was apparent and was funded by a grant on behalf of the Smart Family Foundation. Mrs. Feitler was drawn to the piece because of its beauty. She said that “[it] evokes a calmness and strong statement that was appropriate.”

Truncated Pyramid arrived at the Sculpture Garden in May of 1992. The installation of the sculpture was met with strict instructions about the direction and placement on the site. The work was to completely interact with nature, so the concrete foundation and base support for the piece had to be completely invisible. Highstein ordered that the work appear as though it was resting on the grass. These instructions highlight Highstein’s engagement with the discourse of experience versus knowledge. As an audience member approaches the work we perceive the piece as interacting with its surroundings in a natural way because it is not sitting on a base or propped up to represent it as separate from the landscape around it. The knowledge of the piece as an artwork is completely consumed by its interaction with nature. By resting on the grass in an organic way, the marble sculpture is experienced in the natural context of its materials—outside and interacting with the natural world.

The Smart Museum held a reception to celebrate the installation of the work, which Jene Highstein attended to speak about the piece. The installation of the sculpture was accompanied by an exhibition of a series of Highstein’s large–scale drawings in the Smart Museum, which were on display from June to August of 1992. Highstein’s large–scale drawings accompany most of his sculpture pieces, and were produced with same conception of space in mind as his sculptures were. The drawings were made by hanging the paper on a wall to immediately relate the drawing to space and the human scale. Both the drawings and Truncated Pyramid express changes to a surface (either paper or marble) that transform the material and the viewer’s experience of the work.

Written by Vanessa Farante, 2016

-

Bold Sculpture for Wide Open Spaces (NY Times, July 1989)

Interview with Jene Highstein (BOMB magazine, summer 1983)

Chicago Tribune mention of the installation of Truncated Pyramid

-

Cassidy, Victor M. Sculptors At Work: Interviews about the creative process. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011

Highstein, Jene. Jene Highstein – New Sculpture: October 21-November 24, 2004. New York: Anthony Grant Inc., 2004