“I'm fascinated by the neuroscience of visual perception"

by Danielle Shi, candidate for Masters in the Humanities, MAPH program

Second-year neuroscience PhD student Yuqing Zhu. Photo by Danielle Shi.

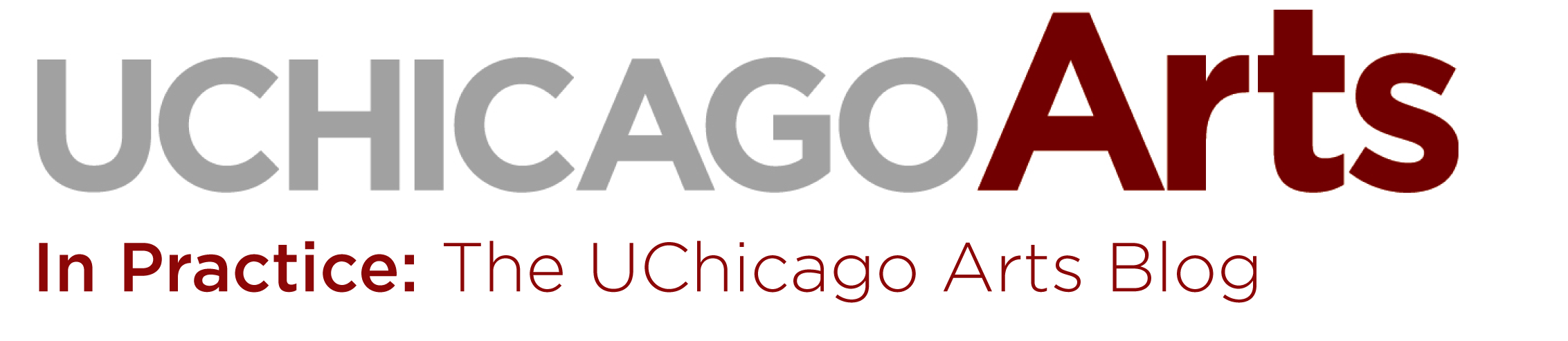

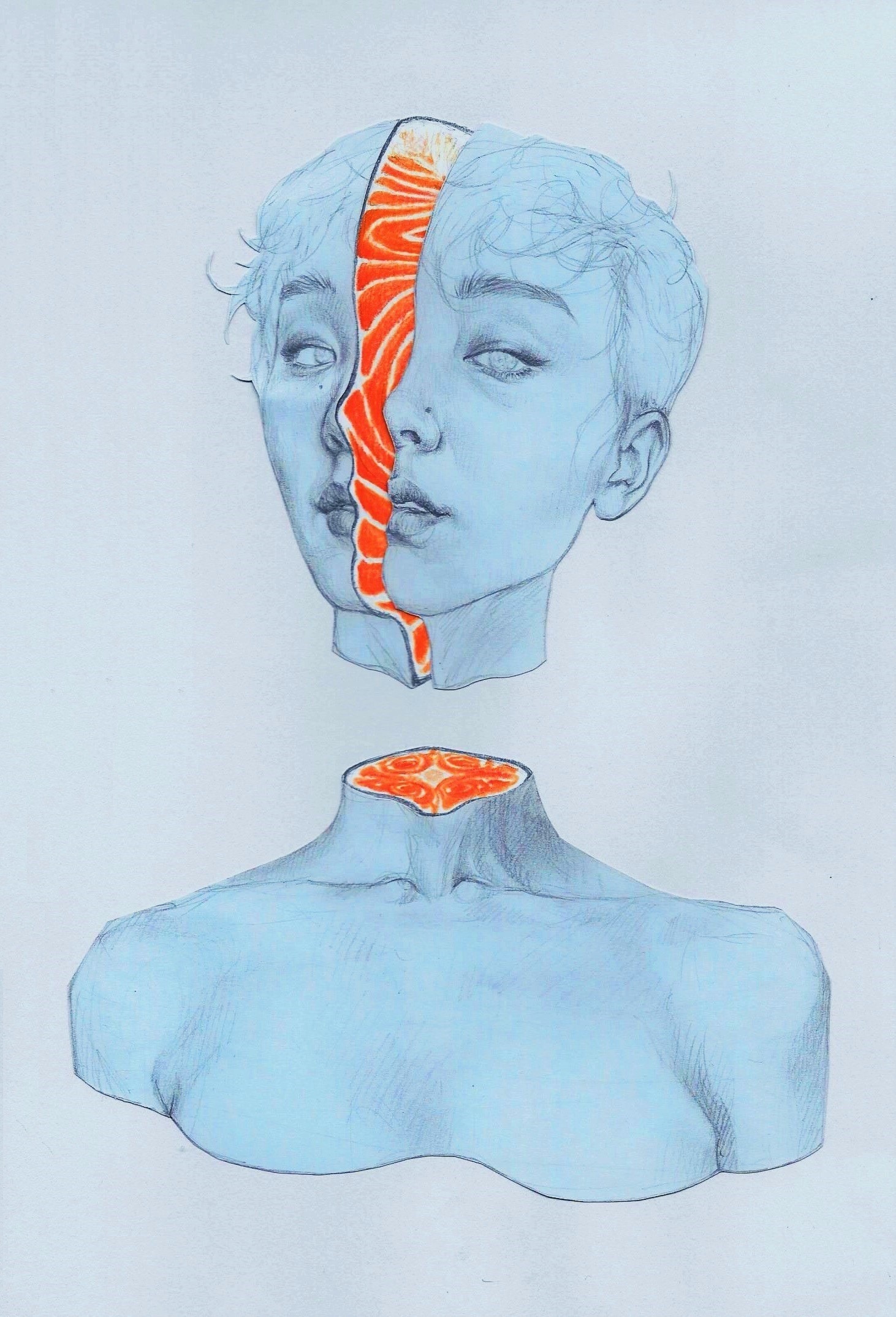

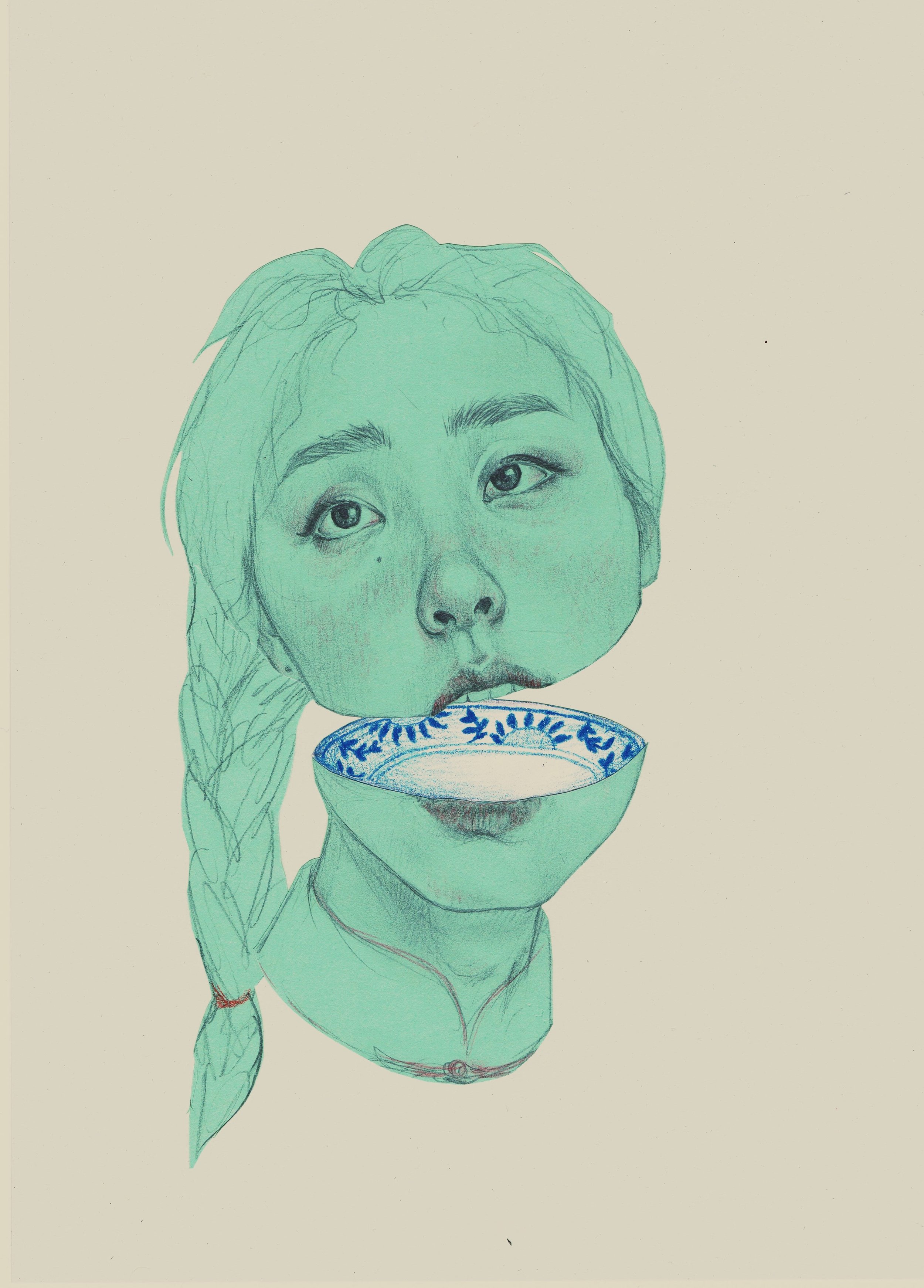

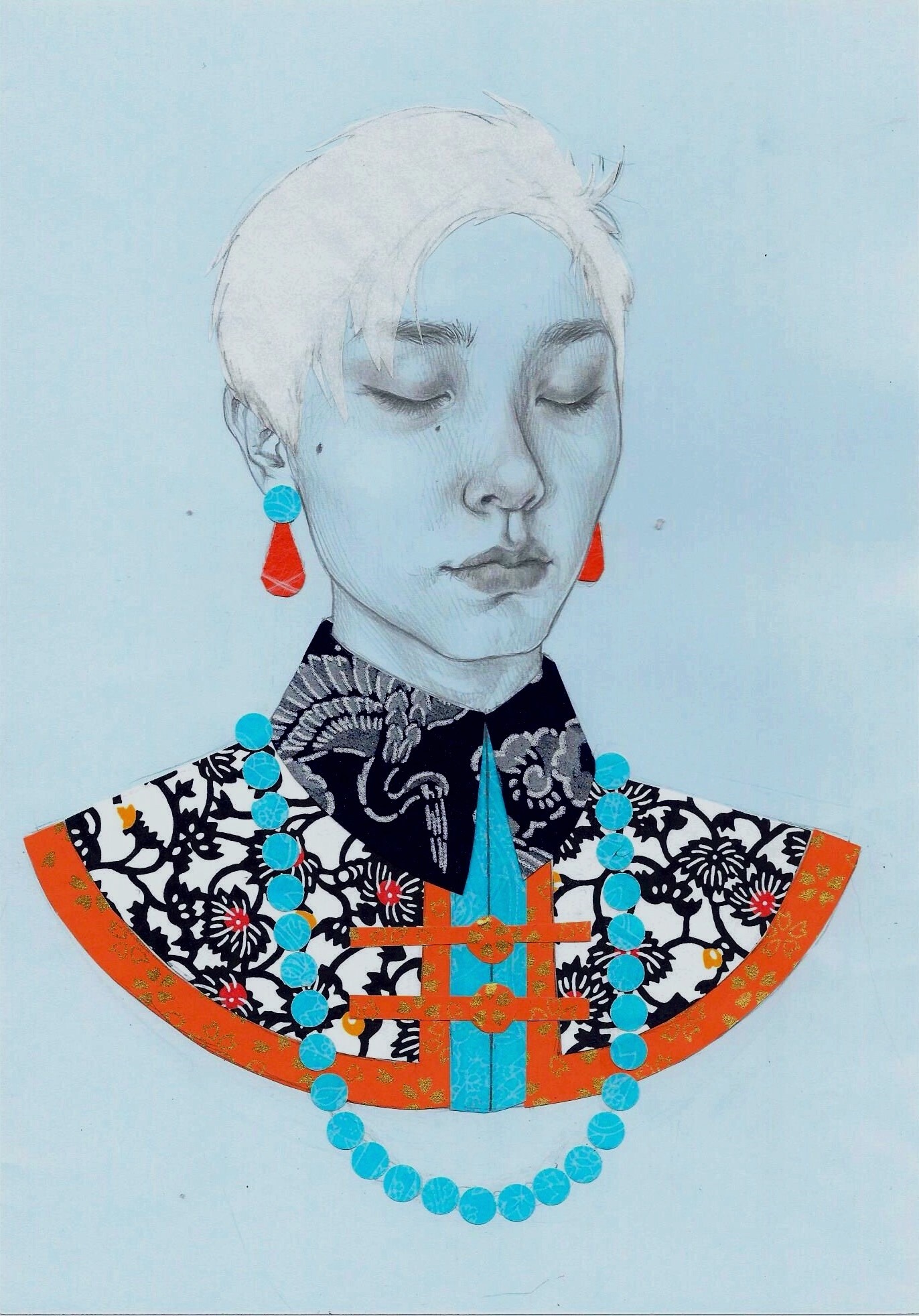

In the living room of her Hyde Park apartment, second-year neuroscience PhD student Yuqing Zhu holds up Precession, her latest artwork of shadowy colonnades, next to a print by Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico. She uses the comparison to point out how her practice alludes to her disjointed Chinese identity as well as Western Surrealists from the early 20thcentury. Yuqing, a first-generation immigrant, relies heavily on her Chinese heritage in her work, drawing characters in fanciful qipaos ( one-piece Chinese dresses dating back to the Manchu era) or wearing Chinese army hats that nod to recent history.

“My reasons for turning inwards [in my artwork] have to do with the inward nature of neuroscience,” explains Yuqing. “My heritage impacts who I am and how other people see me. It may impact what kind of artwork people expect me to create.” She pulls out a black binder from the crowded bookshelves of her apartment and flips through several pages of Surrealistic self-portraits. “But the reason why I draw on it so heavily is because I feel divorced from that part of my identity and this is a way for me to reconnect.”

When she came to the United States at age seven, Yuqing prioritized fitting in at her school in North Carolina, where she lived for a year before moving to Cupertino, California. “At the time, I was very focused on not being Chinese,” she says. “I feel like I robbed myself of something that I had, and now in creating art I’m trying to regain it. In what I do from day-to-day, there’s still no imperative to be Chinese, but if I create something, by making this kind of art, I’m creating a purpose to be Chinese.”

Yuqing’s childhood Chinese art teacher has been hugely influential in her work. “He was very old school; he makes people draw at easels for hours and hours and then will verbally critique and rarely ever give compliments,” she recalls. “He taught me a lot of discipline, to really love creating, and really good technique.”

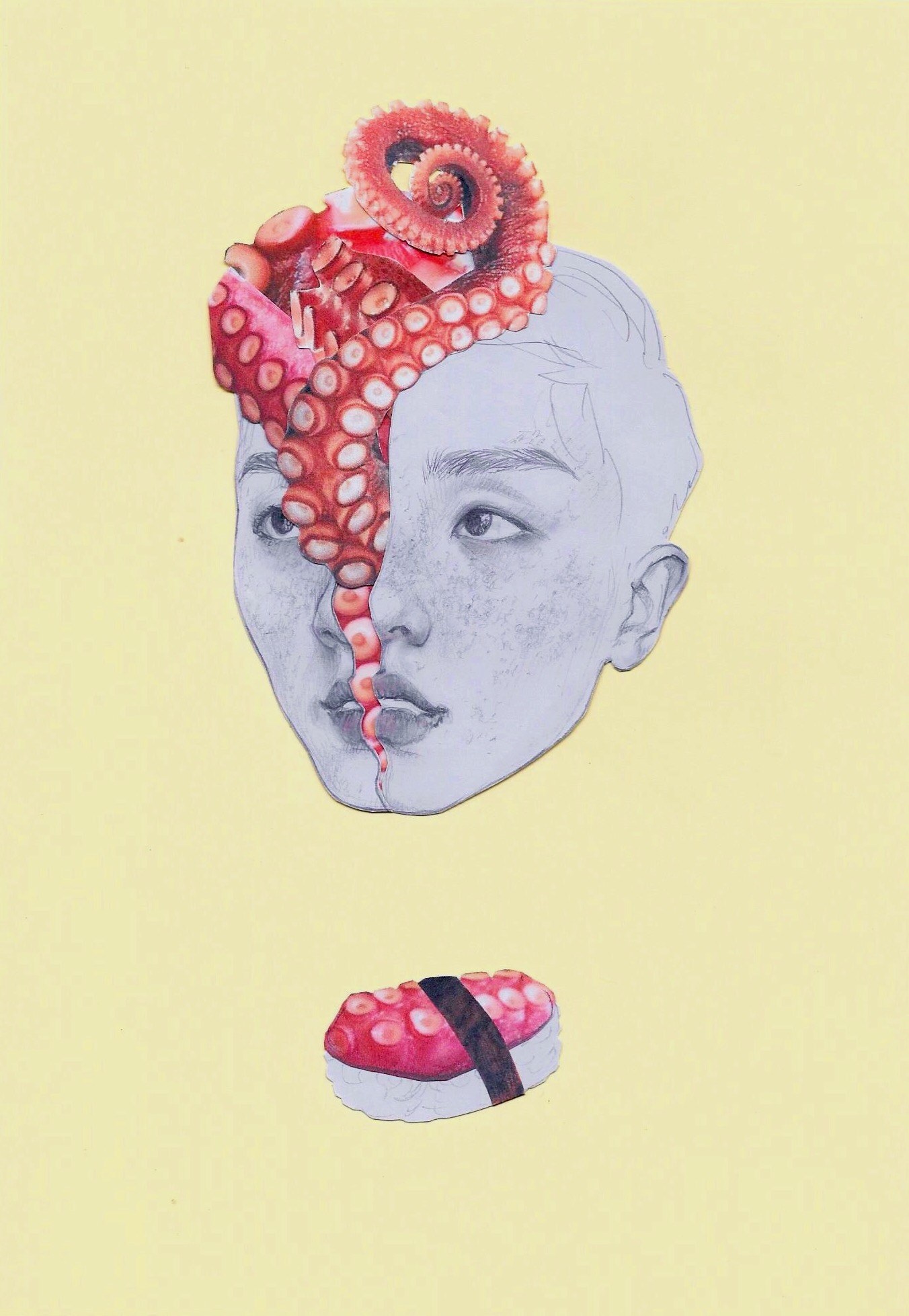

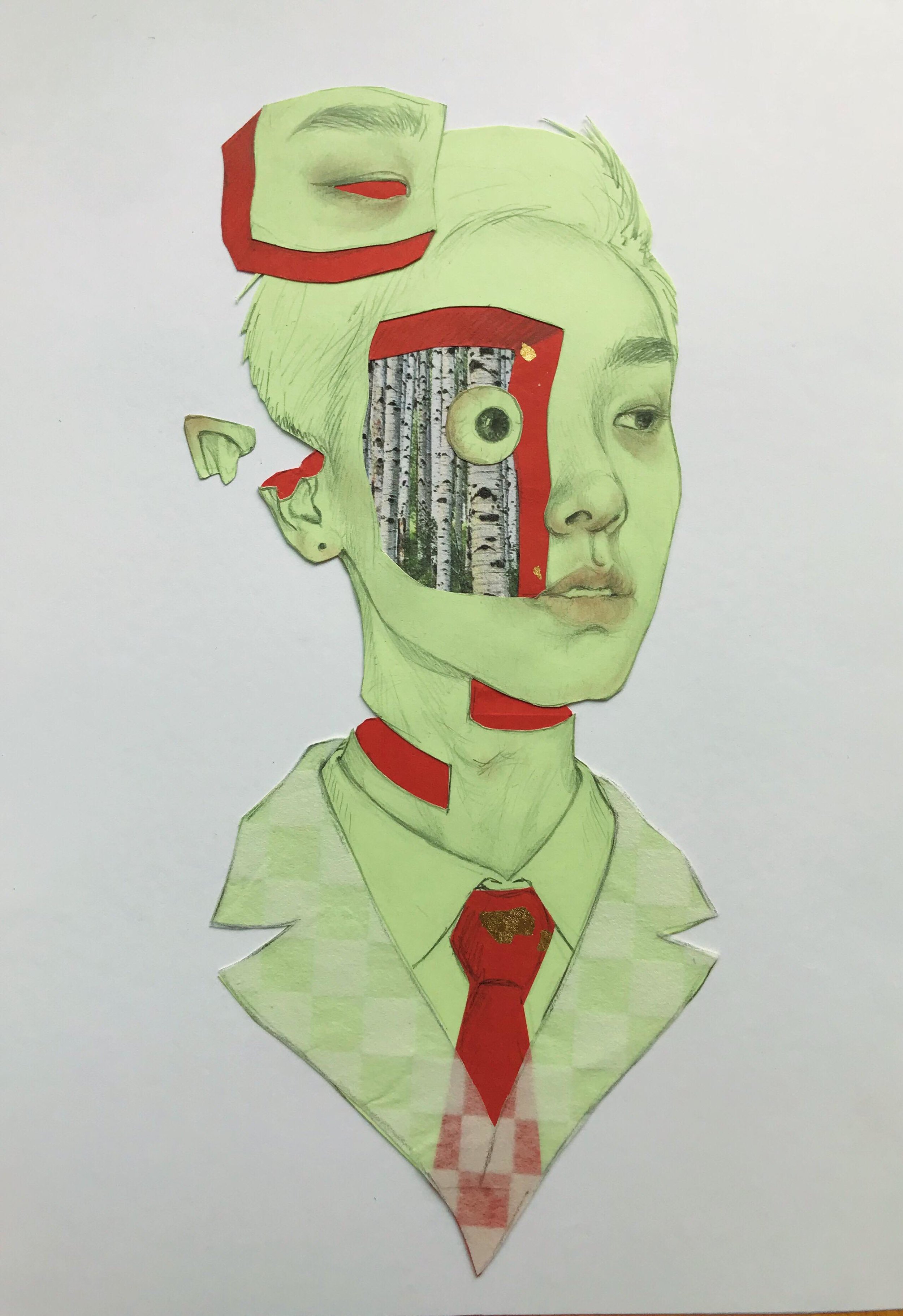

Drawing from this traditional training, Yuqing now uses paper and graphite to make realistic drawings. “Depending on the color scheme that I want, I’ll pick out sheets that adhere to that scheme,” she explains. She prefers the medium of paper, using scissors to compose works instead of being confined to canvas. “I’m most familiar with working on paper,” she adds. “It’s very easy to find, very cheap, and easy to just get going.” She uses atypical loose pigments, such as pots of eyeshadow, which are softer than pastels and good for adding a flush of color to the skin. She focuses on recent Chinese history—her parents’ and grandparents’ generations—because she’s familiar with it through third-person narratives.

Various papers that Yuqing employs in her artwork. Photo by Danielle Shi.

Yuqing reads before she draws, whether about a myth she wants to recreate or the traditional clothes that people wore in a given time period. “I am always reading, and things that I read crop up in my art,” she says, brushing a hand through her short-cropped black hair, another medium for self-expression; she’s dyed it several rainbow hues.

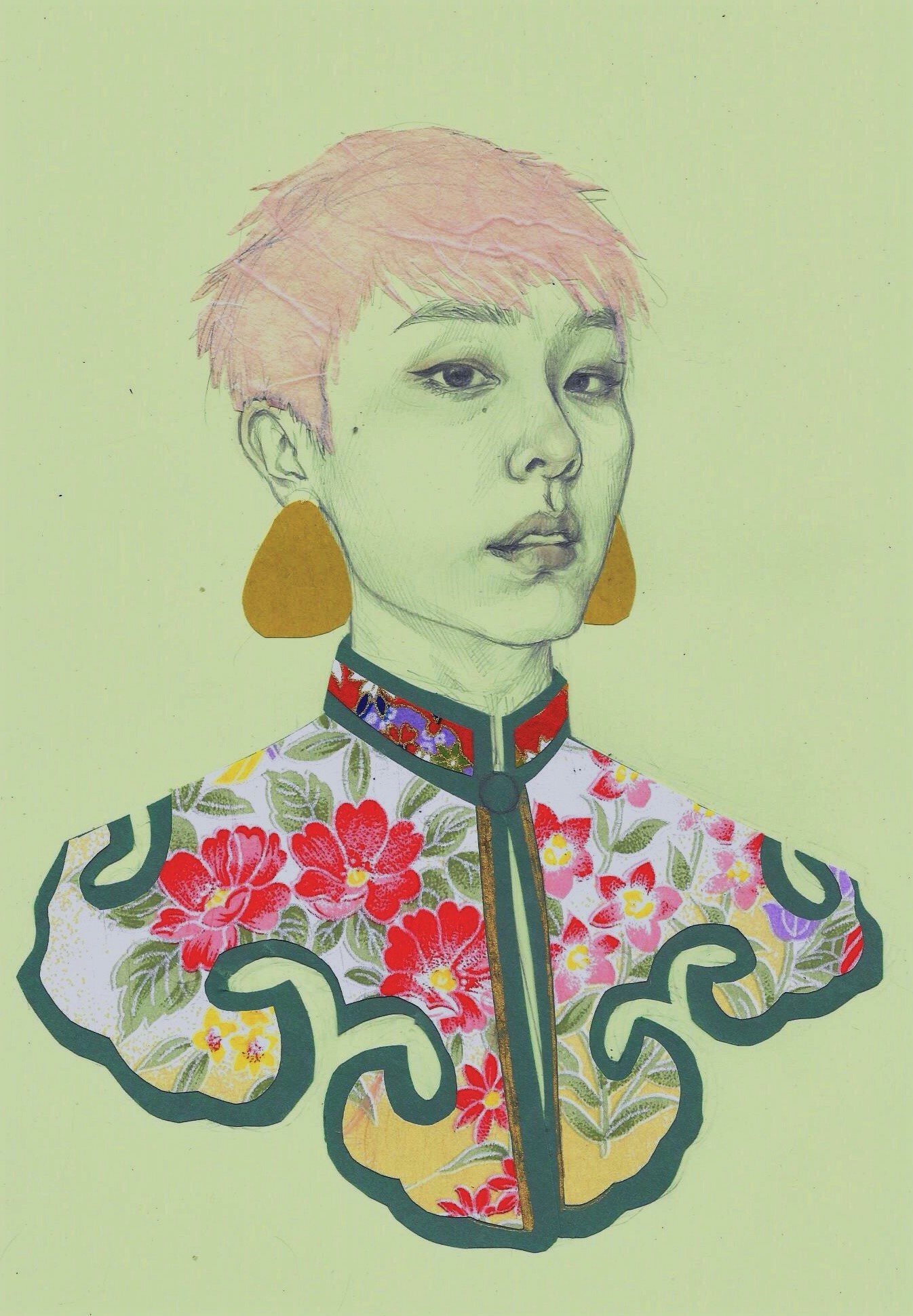

As a student in computational neuroscience, Yuqing works on training computer models to perform visual tasks to better understand vision, decomposing and breaking things to explore what exactly is happening inside the models. The way she makes art and the science she studies are interrelated, she says. “Art and neuroscience require different kinds of effort, but the core of it is just curiosity, expression, and understanding of self. I’ve been studying neuroscience since undergrad, and before that, in high school, I was very gung-ho about being a biologist.” Thanks to her training in neuroscience, she grasps that what she’s seeing is “the manifestation of the physics of light and how that relates to the internal biology of my retina, and how that relates to a whole system of vision.”

Yuqing is often inspired by a fleeting image, a time of year, words, or other art. She made a self-portrait similar to Sir Frederic Leighton’s Flaming June when the title of the painting—depicting a sleeping woman in a billowing orange dress—reminded her of her birth month. In terms of influences, she is particularly inspired by Surrealists like Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, and artists who have made portraits, like René Magritte, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Frida Kahlo. Surrealists, she says, often dealt with the idea of the impossibility of seeing, which connects directly to her scholarship.

“Art and neuroscience require different kinds of effort, but the core of it is just curiosity, expression, and understanding of self.”

“Magritte stated, ‘We always want to see what is hidden by what we see,’ and that is incredibly insightful in terms of sensory neuroscience,” she explains. “I'm fascinated by the neuroscience of visual perception, precisely because of the constructed nature of reality conveyed to us through our senses.”

In addition to these artists, Yuqing looks to the work of late Chinese photographer Ren Hang and other contemporary Chinese artists who live in China, noting that they help her understand that her heritage doesn’t only take place in past tense.

In the fall, Yuqing will teach a course at the School of the Art Institute on light and vision, drawing on her work in the neuroscience field and her lifelong training as an artist. “If you know how vision and light works,” she says, “and how artists have been exploiting our perceptual abilities and the science of how we see things for a very long time, [you have] a more full understanding of what it means to appreciate visual art.”